anatomy of the head and neck pdf

anatomy of the head and neck pdf

The anatomy of the head and neck is a complex and highly functional region, essential for understanding various medical and surgical procedures. It encompasses the skull, facial structure, neck anatomy, and cranial nerves, providing a foundation for clinical practice and surgical interventions. This section introduces key anatomical concepts.

Skull and Facial Structure

The skull and facial structure form a complex framework supporting sensory organs and enabling functions like chewing and speaking. The cranium protects the brain, while the facial skeleton includes bones like the mandible and maxilla, essential for both aesthetics and functionality in the head and neck region.

Cranium

The cranium is the upper part of the skull, forming a protective vault for the brain. It consists of two main components: the calvaria (the roof and sides) and the cranial base (the floor). The calvaria is made of the frontal, parietal, and occipital bones, while the cranial base includes the sphenoid, temporal, and ethmoid bones. These bones fuse during adulthood, creating a rigid structure. The cranium’s inner surface contains grooves and ridges for cranial nerves and blood vessels. The cranial cavity houses the brain, meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid, essential for neural function. Understanding the cranium’s anatomy is crucial for neurosurgery and treating head injuries. Its intricate design balances protection with openings for sensory organs, showcasing evolutionary adaptation.

Facial Skeleton

The facial skeleton is a complex framework of bones that forms the structure of the face, providing attachment points for muscles, nerves, and other tissues. It consists of the upper facial bones, including the maxilla, zygoma, lacrimal, and nasal bones, as well as the lower facial bones like the mandible. These bones work together to create the orbital cavity, which houses the eyes, and the nasal cavity, essential for breathing and olfaction. The facial skeleton also supports the dentition, with the maxilla and mandible forming the upper and lower jaws, respectively. The zygomatic bones contribute to the prominence of the cheeks, while the lacrimal bones play a role in tear drainage. The facial skeleton is connected to the cranial base, forming a seamless transition between the face and the skull. This anatomical relationship is crucial for both functional and aesthetic purposes, enabling movements of the jaw, facial expressions, and sensory perceptions. Understanding the facial skeleton is vital for maxillofacial surgeries, reconstructive procedures, and treating traumatic injuries. Its intricate design reflects the balance between structural support and functional versatility in the human face.

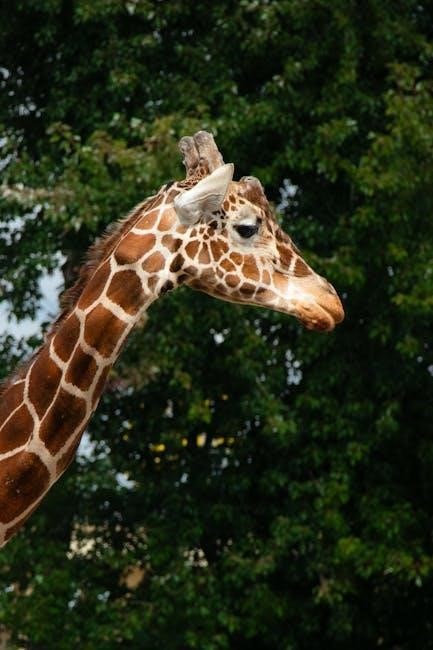

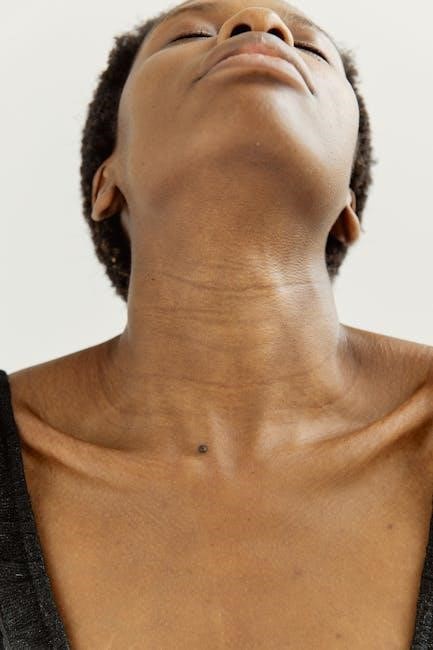

Neck Anatomy

The neck contains vital structures, including the cervical spine, muscles, nerves, and blood vessels. It is divided into anterior and posterior triangles by the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The cervical spine comprises seven vertebrae, with unique features in C1, C2, and C7. This region supports head movement and houses essential organs.

Anterior Triangle

The anterior triangle of the neck is a critical anatomical region bounded by the midline of the neck, the lower border of the mandible, and the anterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It is divided into subtriangles, including the digastric, carotid, and muscular triangles, each containing essential structures. The digastric triangle, located near the mandible, includes the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and submandibular gland. The carotid triangle houses the common carotid artery, internal carotid artery, and cranial nerves such as the vagus and hypoglossal nerves. The muscular triangle, the largest subdivision, contains the sternothyreoideus, sternohyoideus, and omohyoideus muscles. These muscles play a key role in neck movements and swallowing. The anterior triangle is also rich in lymph nodes, particularly in the submandibular and cervical regions, which are crucial for lymphatic drainage. This area is of significant importance in surgical procedures due to its complex vascular and nervous anatomy. Understanding the anterior triangle is vital for surgeons and anatomists alike, as it underpins many clinical interventions in the head and neck region.

Posterior Triangle

The posterior triangle of the neck is a significant anatomical region bounded by the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, the trapezius muscle posteriorly, and the base of the skull superiorly. It is divided into two smaller triangles: the occipital triangle and the subclavian triangle. The occipital triangle, located superiorly, contains the occipital artery and the greater occipital nerve, which are vital for scalp innervation and blood supply. The subclavian triangle, situated inferiorly, includes the subclavian artery and vein, as well as the brachial plexus. These structures are crucial for vascular supply and nerve innervation to the upper limb.

The posterior triangle also houses several cervical nerves, including the spinal accessory nerve, which courses through the triangle and innervates the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. The region is further subdivided by the omohyoid muscle, which separates the occipital and subclavian triangles. This anatomical arrangement is essential for understanding surgical approaches to the neck, particularly in procedures involving nerve repair or vascular access. The posterior triangle’s complex interplay of muscles, nerves, and vessels makes it a key area of study in head and neck anatomy, particularly for surgeons and anatomists. Its detailed comprehension is vital for ensuring precision and minimizing complications in clinical interventions.

Facial Anatomy

Facial anatomy encompasses the structural framework of the face, including bones, muscles, and glands. The facial skeleton provides support, while muscles like the orbicularis oculi and zygomaticus major control expressions. This region’s intricate design enables both functional and aesthetic roles, making it a focal point in anatomical studies.

Muscles of Facial Expression

The muscles of facial expression are a group of specialized muscles that play a crucial role in human communication and emotional expression. These muscles are unique as they are directly attached to the skin, allowing for precise control over facial movements. The orbicularis oculi, zygomaticus major, and risorius are among the key muscles responsible for forming expressions such as smiling, frowning, and blinking. These muscles are innervated by the facial nerve, ensuring their voluntary control. Damage to the facial nerve can result in conditions like Bell’s palsy, which affects facial symmetry and expression. Understanding the anatomy of these muscles is vital for both aesthetic and reconstructive surgical procedures. Their intricate arrangement and function make them a fascinating subject in the study of head and neck anatomy. This section provides a detailed overview of the structure, function, and clinical significance of the facial expression muscles.

Cranial Nerves

Cranial nerves are vital for controlling sensory, motor, and parasympathetic functions of the head and neck. Originating from the brainstem, they regulate vision, hearing, taste, and facial expressions; Damage to these nerves can lead to disorders like diplopia or dysphagia, emphasizing their clinical significance.

Trigeminal Nerve

The trigeminal nerve is the fifth cranial nerve and one of the most significant nerves in the head and neck. It is primarily responsible for sensory functions, including facial sensation and proprioception, and also has motor functions, notably controlling the muscles of mastication. The nerve is divided into three main branches: the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular divisions. These branches innervate the skin of the face, the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, and the muscles involved in chewing. Damage to the trigeminal nerve can result in conditions such as trigeminal neuralgia, characterized by intense pain along the nerve’s distribution. Understanding the trigeminal nerve’s anatomy is crucial for diagnosing and treating various neurological and dental conditions. Its intricate pathways and functions make it a key area of study in clinical anatomy, particularly for surgeons and neurologists. Additionally, the trigeminal nerve plays a role in the transmission of pain signals, making it a target for therapeutic interventions in pain management.

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a bilateral synovial hinge-type joint that connects the mandible to the temporal bone of the skull. It is a complex structure essential for jaw movements, including opening, closing, and lateral excursion. The TMJ is divided into two compartments: the upper (temporomandibular) and lower (mandibular) spaces. The joint is supported by ligaments, such as the temporomandibular ligament, and is cushioned by a fibrocartilaginous articular disc. This disc helps reduce friction during jaw movements and distributes forces evenly. Disorders of the TMJ, collectively known as temporomandibular disorders (TMD), can lead to pain, clicking, or limited jaw mobility. These conditions often result from inflammation, disc displacement, or degenerative changes. Understanding the anatomy and function of the TMJ is critical for diagnosing and managing TMD, which are common issues in dental and maxillofacial practices. The TMJ is also closely associated with the muscles of mastication, which are innervated by the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. This intricate relationship highlights the importance of the TMJ in both functional and clinical contexts. Proper care and management of the TMJ are vital for maintaining oral health and overall quality of life.